RE: UK Crime Statistics Part - 8

Substance misuse

Substance misuse as a public health issue

There is a wealth of research which indicates that substance use is a matter of health rather than proclivity to criminal (read immoral) behaviour. However, policies which pursue substance use as a matter of law rather than vulnerability have been central to the United Kingdom’s approach in addressing this matter. Such a stance has resulted in a deep and complex link between crime and substance use which extends beyond the prohibition and sanctioning of the latter For example, alcohol or substance use, whether used personally or experienced by proxy of a family or household member is defined by the then Public Health England as a key risk factor for children’s exposure to crime. This link is also evident in a bevy of governmental policy and strategy documents; as noted by His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation, “both drug and alcohol misuse are included as offending-related factors”. An academic study identified the drugs-crime association as “an important driver of UK policy, reflected in its prominence in the drug strategies of successive governments”. There are three broad explanations for this association:

Forward causation, wherein the user engages in criminal activity either: (a) to acquire funds for their habit through illicit means, or (b) due to psychopharmacological changes engendered by their use of substances.

Reverse causation, wherein involvement with other types of crime increases the likelihood of contact with and use of drugs.

Confounding, whereby drug use and criminal activity share a common set of causes; there is not a direct causal link between the two but rather a shared antecedent(s).

The study went on to note that underlying causal mechanisms are unlikely to be as simple as this tripartite framework suggests, but rather a more complex set of social phenomena. Irrespective of the causes, for cohorts studied in this research - offending increased correlatively with opiate use. For men, the rate of historical offending for opiate positive cases was almost double that for test-negative controls (rate per year, opiate users: 1.82; non-users 0.91; p< 0.001). For opiate-positive women, the rate was over four times that for test-negative women (opiate users: 1.39; non-users: 0.33; p < 0.001). This is consistent with other studies into substance use and crime.

However, another recent study by Hakansson and Jesionowska shows that the drug-crime association does not equate to a blanket correlation between all types of crime and a history of usage. Factors including a history of binge drinking, use of sedatives, and male gender were positively associated with violent crime, whereas use of heroin, amphetamine, cocaine, and injecting drug use were negatively associated with violent crime. The majority of offences committed by people who use substances are acquisitive in nature, ranging from what has been dubbed ‘non-serious acquisitive crimes’ such as shoplifting to ‘serious acquisitive crime’ such as burglary. Such crimes can be viewed as the outcomes of addiction, relating more strongly to the forward causation identified previously, whereas risk of substance use can be tied to risk of exposure to substances through other criminal activity. The legal framework for ‘drug-related crime’ offers nine categories of offence, including those relating to:

Possession

Supply

Importation

Production

Occupier

Opium

Supply of articles

Inchoate

Obstruction

Offences other than possession undoubtedly cause a significant amount of harm because it enables drug use and therefore puts individuals at risk of health related harms. Furthermore, supply of illicit substances may provide the prerequisite conditions to other criminal behaviour, such as acquisitive crimes, as illustrated above. It should be noted that there are critics who suggest that much of this harm stems from the unintended consequences of prohibition, including the illicit drugs market which was estimated to be worth £9.4 billion by the Government. Whilst addressing the broader consequences of UK drug policy is a matter of significant concern, a more immediate and highly contested issue is whether possession of a controlled substance for personal use only should be decriminalised or even legalised for a variety of reasons..

As of the 31st of December 2022, there were 81,806 prisoners held in England and Wales, 10,855 of which were held on drug offences. After violence against the person and sexual offences, this is the third highest offence category for those in custody. There are more people held in custody for drug offences than for robbery, criminal damage and arson, possession of weapons, and fraud offences combined.

Figure 20: Prison population by offence as of 31 December 2022. Source: Justice Data.

This data source does not differentiate between the three broad categories of drug offences and therefore it is not possible to discern the proportion of the total prison population held for possession of a controlled drug without intent to supply. However, it can be observed from other sources that between 2010 and 2020, a total of 85,358 standard determinate sentences were handed out for all drug offences,10,494 (12.29 percent) of which were for possession without intent to supply. 3,143 of these were for cannabis.

You will have heard many different versions of what it costs to house a prisoner. The Ministry of Justice has two methods of calculating cost per prisoner, either via direct resource expenditure or through overall resource expenditure. 2020/21 figures show that direct resource expenditure per prison was £32,716 per year (£89.63 per day) or £48,409 per year (£132.62 per day) using overall resource expenditure. The average custodial service length for possession of a controlled drug without intent to supply was 2.7 months in 2020.

The United Kingdom has a long history of legislative and regulatory reform with respect to controlled substances. From the International Commissions held at Shanghai in 1909 and the Hague Convention of 1912 to the Misuse of Drugs act 1971 and the Drugs Act 2005, an increasingly so-called ‘hardline’ approach to the use of drugs has developed over time. Such policy is rooted in good intentions with the broad aim of reducing drug production, distribution, and use due to the harm it causes to both the user and others.

However, as evidenced by the aforementioned statistics on the prison population of England and Wales, this has resulted in the criminalisation of people who use drugs in addition to those manufacturing and disseminating controlled substances. Equally, the efficacy of this approach has repeatedly been called into question, not least because the assumption that incarceration is an effective method for reducing the rate of substance use is not steeped in hard evidence. The ‘Prison Drugs Strategy’ produced by HM Prison & Probation Service notes that “the rate of positive random tests for ‘traditional’ drugs’ in prisons increased by 50% from 7% to 10.6%” between 2012/13 and 2017/18. This figure was higher than that identified amongst the non-prison population in the CSEW 2018/19 (9.4 percent). Just think about that for a second. You are more likely to be found to be using an illegal substance if you are in prison than if you are not…

Figure 21: Proportion of adults aged 16 to 59 years and 16 to 24 years reporting use of any drug, any Class A drug and cannabis in the last year, England and Wales, year ending December 1995 to year ending June 2022. Source:Office for National Statistics.

On the point of deterrence, the CSEW indicates that drug use amongst both of the specified age groups has declined, although this is much more pronounced in the 16 to 24 age group. Cannabis use has also decreased more significantly than Class A drug usage in both groups. Whilst an actual decline in substance use may be responsible for this trend in statistics, numerous factors may also impact data gathered from the CSEW. For example, a combination of increased stigmatisation and more severe penalties may result in surveyants becoming less forthcoming with respect to substance use over time - particularly given that those collecting the data are heavily associated with the government responsible for imposing tougher sanctions.

Furthermore, whilst the aim of current policy is to reduce all substance use, the ideal outcome from a harm reduction perspective is to address the usage of Class A substances which, according to the Misuse of Drugs act, carry a greater risk of harm. Had such an approach been successful, the expectation would be that serious harm, including substance-related deaths, would decrease in line with the perceived fall of substance usage. This is not the case.

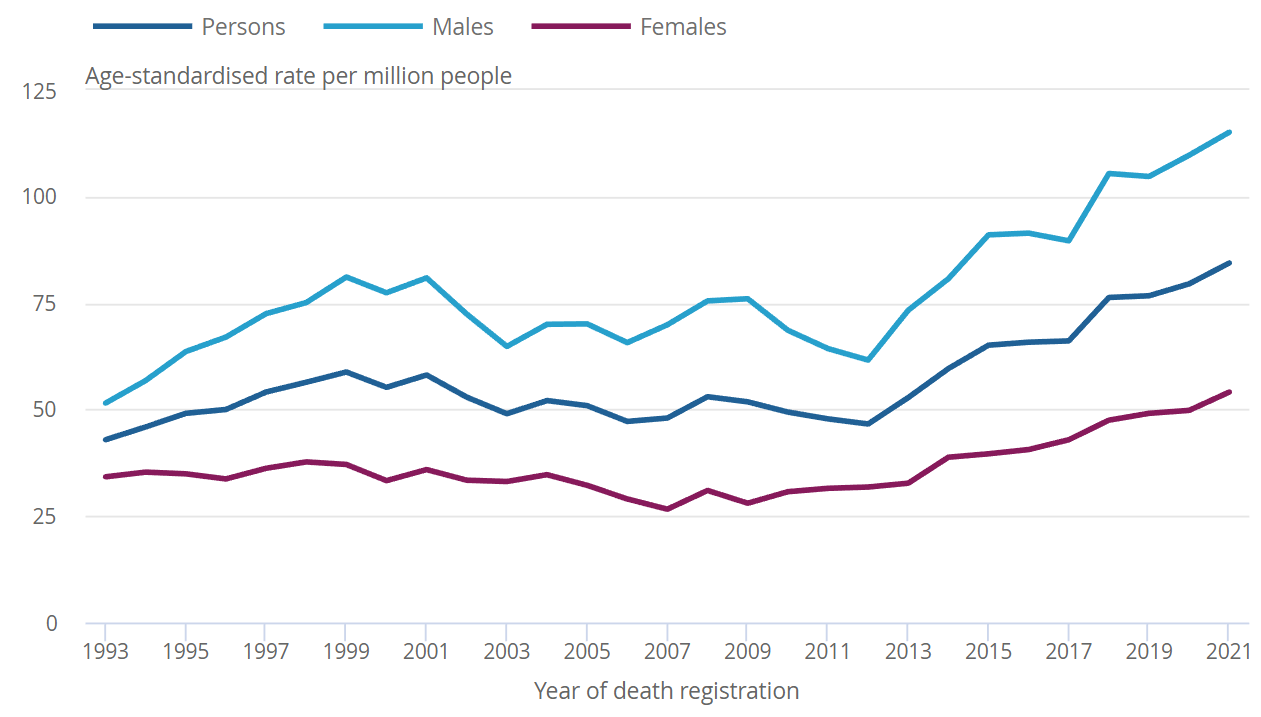

Figure 22: Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales. Source: Office for National Statistics.

Instead, as can be observed from figure 22, the rate of drug poisoning deaths registered in 2021 was 81.1 percent higher than in 2012.

Following Dame Carol Black’s independent report on the approach to and provisions for people that use substances, the government announced ‘From Harm to Hope’, a new ten-year strategy designed to “tackle drugs and prevent crime”. A welcome component of this strategy involves a record £780 million investment into rebuilding the drug treatment system. The strategy also indicates a potential shift towards imposing civil penalties rather than legal sanctions for people that use substances.

Furthermore, the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities has previously noted that, for various reasons, this criminalisation has disproportionately affected young people, particularly those from minority ethnic and deprived backgrounds. From Harm to Hope is therefore likely to positively impact such groups more significantly if the use of out of court disposals (OOCD) scheme is properly and consistently implemented. However, alongside this shift towards support rather than punishment, the Government also announced a White Paper set to explore the introduction of more severe sanctions for those who are repeatedly found in possession of controlled substances. The report notes that “nothing is off the table” with the suggestion that curfews, temporary removal of identification documents, and increased fines may constitute this harsher approach. These suggestions were later fleshed out in the ‘Swift, Certain, Tough: New Consequences for Drug Possession’ White Paper, and now include the possibility of an exclusion order from certain venues or geographical areas.

How do you respond to those found in position? This is the $10 million question. A 1980 study from Critelli & Crawford examining reoffending rates for individuals convicted of a range of offences found that “subjects receiving a fine had a higher probability of future crime than those receiving no punishment”. This also scaled with the severity of the sanction, with those receiving “a comparatively severe fine” having a higher likelihood of recidivism than those receiving fines which were small compared with the suggested fine for that crime. Data from the Ministry of Justice for the 2019/20 shows that, whilst the proven reoffending rate for those who are fined is lower than several other types of sanctions, those receiving only a caution were shown to have both the lowest reoffending rate and the lowest average number of re-offences per person.

In the specific context of substance use recidivism, Alexeev & Weatherburn published a study in 2022 exploring the effect of fines on reoffending rates for re-offences of any type, use/possession re-offences for any drug, and use/possession re-offences for the same drug involved in the original offence. For each of these dependent variables, the use of fines as a sanction increased the likelihood of reoffending, although by a statistically negligible amount.

Figure 25: Fine and reoffending in 0-2 years: main estimates. Source: Alexeev & Weatherburn, 2022.

Unhelpfully, the evidence for the efficacy of fines as a deterrent for substance use is limited. We have a drug problem in the United Kingdom, particularly in Scotland but a problem throughout. The solutions to this in the context of tackling crime are not straight forward. We need some honesty about this if we are to tackle this issue. Let me know what you think needs to happen.