RE: UK crime statistics. Part 2

A longer term funding settlement

Police Funding

There are several key areas of debate concerning the police, including those concerned with the funding, size, deployment, purpose, remit, and organisation of the institution. This section of the report will address each of these factors in turn, although there are significant intersections within and between.

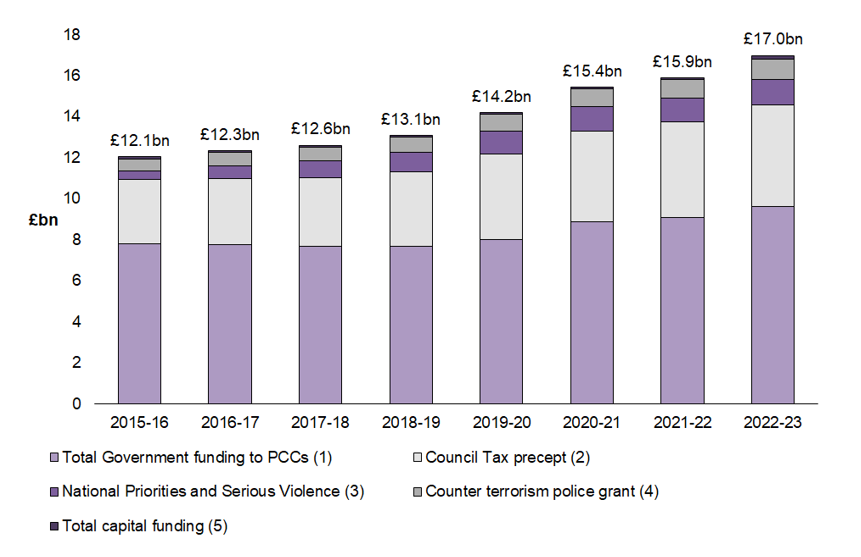

As a public sector institution, funding for the police is subject to constant review and revision, resulting in frequent debates and disputes concerning the Government’s decisions. For a significant portion of the 2010s, budgets for policing decreased substantially, driven largely by austerity measures. The Institute for Government argues that “the police in England and Wales have had to adjust to large cuts in funding from central government”. For example, the National Audit Office identified the £7.7 billion received by Commissioners in 2018-19 as “30% less than they received in 2010-11 in real terms.” Ostensibly, overall annual spending for policing has increased year on year since the financial year of 2015-16 from £12.1 billion to £17.0 billion or £17.2 billion, depending on the source. However, taking just this figure into account does not paint the full picture. Data from the Home Office shows that the composition of this funding has changed significantly alongside this increase, with a significant proportion of additional funds being leveraged from the council tax precept, as can be observed from Figure 4.

Figure 4. Overall annual funding for policing since the financial year ending March 2016 (nominal). Source: Home Office.

It is not simply the size of the overall funding, but how it is structured, decided upon, and disseminated that results in disharmony between the police and central government. One such issue is that said funding is awarded as a one-year settlement, a predicament which the Police Federation argues will cause the institution to “struggle to make sustainable and significant plans beyond next year”, limiting its ability to “prepare for the future and take advantage of procurement economies of scale over multi-year contracts”. This push to update the timescale of funding arrangements for the police is not new and can be traced back at least as far as 2019 in which His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Resource Services (HMICFRS) encouraged the newly elected assembly to “recognise the need for a long-term approach to police funding” which would “enable police leaders to make long-term investments.”. In 2018, the Home Office noted that Police and Crime Commissioners were spending almost a quarter of their overall budgets on goods and services with third party suppliers - an area which could be better addressed if police forces were able to adapt their procurement to longer funding cycles. As such, the Home Office should consider bringing funding arrangements for the police into alignment with other public sector institutions like the National Health Service, extending the settlement from 1 year to 5 years. This would support the national agenda for cost efficiency savings.

As can be observed from figure 4, a significant proportion of the funding from the police is derived from the council tax precept. £4.9 billion of the £17.2 billion awarded to police forces across the country for the financial year 2023-24 originates from this source. However, there is significant variation in the proportion of total funding represented by the council tax precept between the 43 territorial police forces across England and Wales. For example, in 2022, 28 percent of Cleveland Police’s funding was derived from the council tax precept compared to 55 percent for Surrey Police. This means that changes to the size of central funding has a drastically different effect on police forces depending on their ability to leverage funding from their respective local authority. Furthermore, prevalence of crime is typically concentrated in areas which suffer higher rates of income deprivation. This effect can be observed as particularly significant in London, as between January and December 2022, 125,619 crimes were recorded for neighbourhoods in the most deprived decile for income, compared with 82,760 crimes for neighbourhoods in the least deprived decile for income. This represents a staggering increase of 51.7 percent. Simultaneously, it is these neighbourhoods in which council tax is likely to be lower, largely due to lower house prices.

Figure 5: Crimes recorded by neighbourhood income deprivation decile in London (January 2022-December 2022). Source Trust for London.

The police allocation formula (PAF) has been critiqued for the additional reason that it is based upon data that is a minimum of “nine years out of date”, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, This includes population data, used in part as a proxy for crime demand. However, the dataset utilised is derived from the 2001 Census which has since been updated twice. This has the potential to skew the police allocation formula, particularly given the differential trends in population growth. The population in London has grown by 7.7 percent between 2011 and 2021, compared with 3.7 percent in Yorkshire and the Humber and 1.4 percent in Wales.

Figure 6: Population change, 2011 to 2021, Wales and regions of England. Source: Office for National Statistics - Census 2021.

Reform of the PAF was attempted in 2015, but failed for a number of reasons. At the time, three options were considered: continue with current practice, upgrade the existing PAF, or create a new and simplified model based on a broader range of factors. The Home Office ultimately concluded that the first option “would move force level funding allocations further away from relative need” and that the second “suffered from a number of unresolvable issues, and did not accord with the Government’s principles of a good funding model”. Therefore, a new model was required, one which could “help explain why the demands on police differ between force areas so that relative of required resources can be determined”. However, over seven years have since passed with no sign of reform of the PAF. One of the most significant criticisms of the review at the time concerned the consultation process, specifically the purportedly rushed timescale and lack of transparency over the data underpinning the suggested changes. In the interest of achieving a successful reform process, one that reflects the significant changes that have occurred since the last attempt, it is recommended that consultation for a new review begins as soon as possible. It is equally important that the Home Office, Police and Crime Commissioners, and police forces more broadly work collaboratively to achieve an outcome which is fair by consensus.

Strength of the Police Force

One of the most significant contentions regarding the police is the number of officers in-post from a singularly quantitative perspective. Different accounts offer slight variations in the exact statistics for serving police officers over time, though there is consensus that the wave of austerity introduced in 2010 by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition set against the 2008 financial crisis resulted in a substantial decrease in the overall number. A statistical bulletin from the Home Office in 2019 showed that in 2010, this number peaked at 143,734, and fell each year until 2018, at which point there were 122,405. In 2019 this number began to climb again, due in part to the pledge by the then incumbent Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, to hire 20,000 police officers by the year 2023.

Figure 7. Number of serving police officers in England and Wales 2010-2019.

In November 2022, a publication from the House of Commons Library placed the figure at 140,228, significantly closer to the peak value in 2010. However, at the time the pledge by Johnson was made, the Institute for Government noted that the changing mix of crime in recent years including the “steep increase in complex and violent crimes means that deploying additional police on the streets may not be appropriate”, and that complex crimes such as fraud and sexual offences often require “more substantial involvement from other types of police staff including those working in operational and business support.”. Contrastingly, in London over 90,000 mobile phones were stolen over the last year, the equivalent of 1 every 6 minutes. When it comes to policing, the solution must be more officers on our streets and more officers within operation and business support roles.

Academic evidence to date has struggled to identify and prove a strict cause and effect relationship between the number of serving police officers at a given moment and a reduction in overall crime. Rather, a range of studies, including systematic reviews tend to produce inconsistent results, comprising positive, negative, and null associations between the number of police officers and the level of overall crime. The most recently available review of evidence was performed by Ben Bradford in 2011, performed on behalf of HMICFRS. The review examined 13 pieces of research and concluded, broadly, that much more evidence is required if a causal link of this nature is to be established. However, evidence from a select few of the studies tentatively suggests that a 10 percent increase in officers is associated with a 3 percent reduction in property crime. This is thought to be due to the fact that this type of criminal offence is more highly calculated in terms of cost-benefit, factoring in the presence of police officers as a potential antecedent to sanctions. Other types of crime, such as violent crime, do not appear to have a similar association; this is thought to be due to the often emotional motive which fuels such situations. Whilst this rapid evidence review is the most recent and comprehensive analysis of the link between police numbers and levels of crime, there are two key considerations which support the case for further investigation. Firstly, 11 years have elapsed since the review took place, during which a number of factors critical to such an evaluation have fluctuated significantly. This includes the overall levels of crime and the proportion of crimes which comprise this statistic, as well as the size of the police in England and Wales. Secondly, it is significant that a sizable majority (11/13) of the studies considered for review took place in locations other than England and Wales, including the United States of America, the Netherlands, and Argentina. Each of these locations has a distinct social, cultural, and political context informed by historical events such as interactions between the population and the state and, by extension, the police. This may ultimately detract from the validity of analyses to date and illustrates the necessity to undertake studies specific to England and Wales as a discrete jurisdiction. It would therefore appear that academic evidence to date is inconclusive on what the future size of the police as an institution should be in terms of numbers. Given the growth of complex crime, it is, however, evident that future investment should ensure sufficient personnel extra to the body of serving police officers, including business support and administration. There is also a point to be made about public sense of safety. The College of Policing notes that in the UK, there is “a strong preference for a highly visible police presence” driven by “a desire to see crime reduced”. Simultaneously, evidence to date indicates that patrolling areas “has no effect on crime reduction”. It is therefore in the interests of both the public and the police to arrive at a solution which accounts for this preference without squandering resources on ineffective deployment, an end which may ultimately be best served through an absolute increase in police numbers. .

As the evidence for this topic is inconclusive, It may therefore prove more fruitful to examine instead how the extant resources of the police may be deployed more effectively to respond to trends in crime and their underlying causes. At this point it is important to state that the substantial decrease in certain offences does not warrant a reduction in the resources and attention afforded to them. After all, 1,151,000 violent crimes and 2,686,000 thefts are no small numbers. Rather, this paper is concerned with what has worked previously to achieve such a reduction, and which strategies may be employed in future to achieve a reduction similar in scale with respect to other types of crime.