RE: UK crime statistics

What crime data tells us

Crime continues to concern citizens in every part of the United Kingdom. We know that people feel less safe, and that the nature of crimes committed has evolved. But to truly be able to future-proof our country we must delve deeper into what exactly is happening, and so today we launch a new series “Future-proof Tackling Crime”. Part 1 will focus on digging into the data over a period of time. A big thanks to my researcher Conor for his assistance with this:

Data Quality:

Data quality poses a significant barrier to the endeavour of tackling crime as numerous factors, such as how crime is reported, recorded, and sentenced, impact upon the reliability and accuracy of available information. For example, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) notes that increases in metrics including “both the rate and Severity Score for most police forces are likely to reflect recent improvements in recording practices”, rendering data prior to 2014 less reliable. Equally, environmental factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic pose a threat to the continuity of such data. This can be observed in that designated national statistics on the prevalence of crime for the period between March 2020 and June 2022 are unavailable due to interruptions to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW). This leaves a relatively short snapshot of reliable data to work with. As a result, a range of additional data sources will be considered and integrated in order to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the current systems for understanding and responding to crime in England and Wales. However, considerations of the validity of this data will be maintained throughout.

What has been published by the ONS speculatively suggests a statistically significant decrease of 8 percent in the overall prevalence of crime affecting individuals aged 16 years and over in England and Wales since the previous recording period (the year ending March 2020). As noted above, this data may not be a true representation of crime in the jurisdiction due to a range of factors; data was recorded over nine months instead of the usual 12 and response rates were lower than in previous years. Other sources, such as CrimeRate, suggest the crime rates per 1,000 people are 77.49 and 75.19 for England and Wales respectively. In turn, these figures represent increases of +5.86 percent and +4.86 percent respectively and were reported by media outlets as “an all-time high” in 2022. It should be noted, however, that police recorded crime data are “not designated as national statistics”, and as such, cannot be considered authoritative to the same extent as the CSEW.

Prevalence of Crime Over Time

The impact of crime is judged using a range of methods due to the various different sites in which these costs are borne out. Whilst crime in itself is harmful, the secondary effects often exceed the scale of the act in terms of damage to individuals, communities, institutions, and society overall. The most recent available data for the economic impact of crime at the national scale, provided by the Home Office in 2018, estimated the combined cost of commercial crimes and crimes against individuals to be £58.8 billion per year. Despite this staggering cost, there is some data, such as that provided by the CSEW, that suggests that the (overall) prevalence of crime has decreased since the inception of the survey in 1982, at which point 11,303,000 crimes (excluding fraud and computer misuse) were recorded for the previous year. Whilst this figure increased significantly up until December 1995, at which point it peaked at 19,786,000, it has decreased steadily ever since to stand at 9,390,000 in June 2022. The cost of living crisis is likely to result in an uplift in crime rates, as Chair of the John Lewis Partnership - Sharon White – has recently attested to.

More recently, however, additional metrics have been introduced as a means of understanding not just the prevalence of crime, but also the scale of its impacts. One such measure includes the Crime Severity Score (CSS). The CSS is based on judicial sentencing measures and was developed to complement police recorded crime with a view to measuring change over time and between regions. Such data extends as far back as the period between April 2002 and March 2003, at which point the CSS was 15.9. This dropped year on year to 9.3 for the period between April 2012 and March 2013, at which point the CSS began to rise again steadily (with some fluctuations) until the most recent recording period of April 2021 to March 2022. Presently, the CSS has resumed its peak value of 15.9. Whilst the CSS provides valuable insight into additional dimensions of the impact on crime, due to its reliance on sentencing measures, the metric may be skewed by changes in severity of sentences commensurate with crimes. For example, the average length of a prison sentence has increased from 13.8 months to 18.9 months between 2009 and 2019. The Criminal Justice Act 2003 also resulted in significant inflation of sentences for murder, with sentences having increased since by an average of nine years. Nevertheless, this combination of CSEW and CSS statistics suggest that, while the total number of crimes have ostensibly decreased, the associated impact upon victims has increased inversely as can be observed from Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Crime Survey for England and Wales and Crime Severity Score 2011-2021.

Whilst based on figures not designated as national statistics, the trend observed above bears investigating further.

Mix of Crime

One possible explanation for the simultaneous decrease in CSEW estimates and increase in CSS is that the blend of crimes being reported has changed over time. A greater prevalence of crimes deemed more serious or lesser prevalence in crimes deemed less serious, according to the CSS, could account for such a pattern.

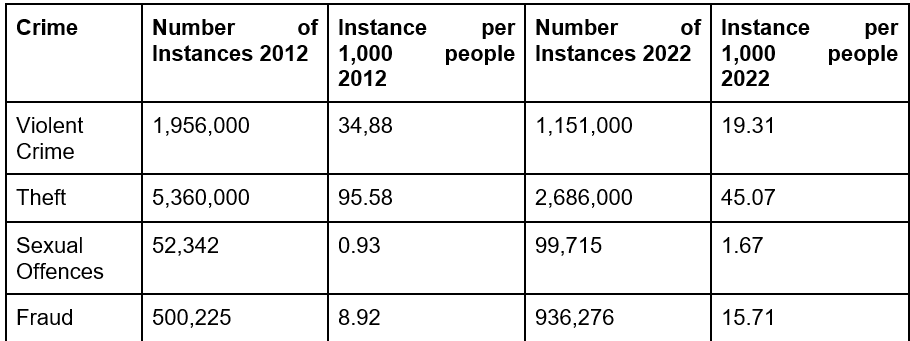

Figure 2. Prevalence of selected offences 2012/2022. *Data for sexual offences in 2022 covers only Q1-Q2; actual number expected to be significantly higher. **Comparable data for fraud exists from 2014 onwards which is displayed here. Source: Office for National Statistics.

As can be observed from Figure 2, there have been significant changes in the proportion of certain offences. For example, overall violent crime has reduced significantly from 1,956,000 incidents to 1,151,000. The same is true of overall theft, for which instances have almost halved from 5,360,000 to 2,686,000. Conversely, the prevalence of other types of crimes has grown substantially. 99,715 sexual offences were recorded for the first half of 2022 alone, nearly double the 52,342 recorded for the whole of 2012. Fraud has also burgeoned since 2014, in which 500,225 instances were referred to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB). In 2022, this number was 936,276. Absolute numbers may not tell the full story, however, as instances of crime can be expected to scale with population size - at least to some extent. Instead, it may be more accurate to examine the crime rate per 1,000 people using Census data from 2011 and 2021.

Figure 3. Comparison of crime rates per 1,000 people for selected crimes for 2012 and 2022. Source: Office for National Statistics.

Changes to the profile of England and Wales’ criminological landscape are even more stark when presented in this fashion. Said changes are largely driven by social, cultural, and material shifts in human behaviour. For example, the 2017 ‘#Metoo’ movement and its derivatives such as ‘Everyone’s Invited’ saw a significant rise in reporting to the police which was described by Kate Ellis, a legal professional, as “an indication of victims feeling they will be believed and supported”. This in turn led to the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) as well as the Women and Equalities Select Committee holding consultations respectively, with the Wera Hobhouse MP bringing forward a Government-backed Private Members’ Bill to introduce protections making employers liable for failing to prevent third party harassment. This series of events clearly demonstrates that social and cultural attitudes towards the systemic efficacy, sincerity, and celerity of those that would receive their disclosure are critical factors in how crime is understood at a given moment. This can be observed more clearly in police recorded crime data as they encapsulate both current and retrospective accounts of offences, whereas CSEW data concerns the past 12 months.

Equally, environmental factors account for a significant proportion of trends in criminal activity and commensurate reporting. Most notable in recent years was the pandemic which saw many isolated from their usual support networks and drove up internet usage, leaving many with little choice but to resort to undertaking their usual activities such as shopping and communicating in digital format. Ofcom shows that the average daily time spent online among adults in the United Kingdom rose from 209 minutes per day to 242 minutes per day. By the end of 2021, incidents of fraud had increased by 32 percent from the previous year, in particular consumer and retail fraud. Additionally, incidents of computer misuse rose by 85 percent, largely driven by unauthorised access to personal information - including hacking. On the other hand, crimes which typically require physical contact such as theft and robbery decreased. What is clear from the influence of such factors is that the current systems for policing and litigating crime are vulnerable, both to their past inadequacies and to volatility within and beyond the environments which they govern. Future efforts to tackle crime must be connected enough to these environments if they are to be successful in understanding changing trends in criminal activity and civilian demands as well as adaptable enough to respond where necessary. Subsequent sections of this report will examine how current approaches to policing, justice, and crime as three key areas of criminology may be adapted and improved in future.