RE: UK Crime Statistics - Part 7

Are school exclusions necessary or part of the problem?

Reducing exclusions for all children

Kids are now back at school, hurray - but some children will not last a full year… some might not even last the term. I remember during my time in Downing Street having two very interesting meetings. The first was with the then head of Ofsted - the school inspection body. She said that she did not believe there was a clear correlation between school exclusions and the criminal justice system. I then met with the the head of the Met Police, who said the correlation was clear. So who was right?

I’m afraid the evidence I have seen shows that the correlation is very clear. Perhaps, the the head of Ofsted was trying to articulate that the issues that lead to a child’s exclusion are often things that most schools are not equipped to deal with and/or responsible for. Therefore, the exclusion in and of itself is not the cause - and that a child’s outcomes are unlikely to change even if they are allowed to remain in a school. Others within a class are the ones that suffer. Whilst I can appreciate this position, particularly with the challenges teachers face on a daily basis - we should all be afforded the opportunity of the full context before coming to conclusions on this important subject. Which you will hopefully receive now. Let me know what you think of the below…

The National Education Union (NEU) notes that whilst “there can be no dispute that schools must do all they can to ensure the safety of learning environments”, there is little evidence that zero tolerance approaches to discipline in schools engenders positive behavioural outcomes. On the contrary, uses of these systems “have had a highly negative and exclusionary impact on black students and on students with SEND and on FSM” and “may boost the school-to-prison-pipeline”. Instead, the NEU makes several recommendations that can be grouped into four broad categories.

Approaches to disruptive behaviour: schools should implement a graduated system which corresponds sanctions to the severity of behaviour.

Constructive practice: the first recommendation should be introduced alongside initiatives that seek to rebuild the school bond for students at risk of behaviour problems or violence such as restorative justice programmes.

Multi-agency working: efforts should be concentrated on improving collaboration between schools, parents, youth offending teams, and mental health professionals to develop early interventions and alternatives to isolation and zero tolerance.

Learning and development: schools should invest in continuing professional development for staff to develop trauma informed practice and an understanding of the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

Reducing exclusions for minority ethnic children

It is a known quantity that ethnic diversity amongst teachers is severely limited across Britain. At present, 70.5 percent of the working age population is white British. For the teacher workforce, this figure is 85.1 percent. Furthermore, the Hamilton Commission of 2021 found that 45 percent of schools in England had no racially diverse teachers at all. This disparity is even more concentrated at the senior levels of the education sector. 92.7 percent of headteachers are white British, 0.2 percent are black African, and 0.7 percent are black Caribbean. Experts argue that increasing the ethnic diversity of school teachers will provide role models for minority ethnic children and support increased educational attainment.

Whilst there is little domestic research available about the impact of diverse teaching staff on the exercise of disciplinary action against students, a recent study based in the USA indicates positive results. Two key findings: First, “greater racial and ethnic diversity on district teaching faculties was associated with a reduction in suspension disparities. As such, increasing representation in the teacher workforce may support a reduction in “inequitable imposition of social control in schools”. Second,”as racial and ethnic teacher diversity increased, the threatening environment that is often associated with higher percentages of minority school students was mitigated, which in turn decreased racial and ethnic suspension disparities”.

This research builds on a body of literature in the USA which also suggests improving representation can engender positive outcomes for minority ethnic students. There are findings which indicate that “student disciplinary outcomes are less severe when they are assigned to a teacher of the same race or ethnicity”, which suggests that severe sanctions such as suspensions or exclusions might be metered out less frequently with increased ethnic diversity amongst teachers. Downey and Pribesh also showed that “when the teacher’s race matches that of the student, they had more improved perceptions of their behaviour”, confirming that the perception of bad behaviour could be amplified by a lack of diversity in the workforce. Finally, another study found that “greater board diversity at the district level decreases punitiveness in schools”, which could suggest that local governing boards, as well as senior leadership teams and the wider teacher workforce could be areas of focus with respect to ethnic diversity in schools.

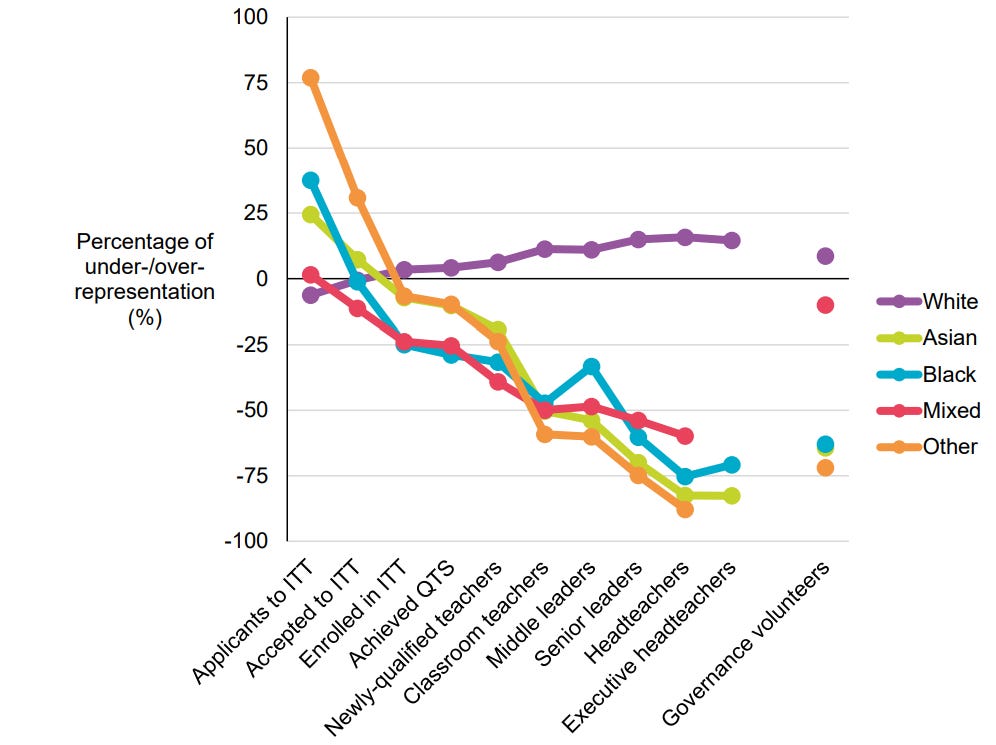

There is a clear lack of diversity in teaching and clear benefits to addressing this challenge. However, recent research by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) has demonstrated that the lack of representation across the profession is unlikely to be caused by a lack of engagement from minority ethnic groups. Rather, Asian, black, mixed/multiethnic, and other minority ethnic groups are all overrepresented within applications to initial teacher training (ITT). What follows is a stark drop from this stage through to enrollment in ITT. This downward trend continues onwards as seniority increases.

Figure 17: Over/under representation of ethnic groups at different stages in the teaching profession. Source: National Foundation for Education Research.

Evidence shows that it is not that people from minority ethnic groups do not want to become teachers. Despite an overrepresentation of Asian, black, mixed/multi-ethnic, and other minority ethnic groups in applications to postgraduate ITT courses, acceptance rates vary significantly. 66 percent of people from white ethnic backgrounds have their applications accepted at this stage, compared to 57 percent of mixed/multiethnic applicants, 53 percent of Asian applicants, and 45 percent of applicants from black and other ethnic groups. These gaps have narrowed considerably between 2013/14 and 2019/20, and are smaller in London than in other areas, which indicate some progress over time. However, these disparities remain unexplained and must be examined if representation in the teaching profession is to improve. The NFER has urged the leaders of ITT providers to make two key changes. Firstly, they recommend that each provider review their recruitment and selection processes to understand why these disparities exist and remove barriers to entry for minority ethnic applicants “at this crucial first stage of entry into the profession”. Secondly, larger educational organisations (such as colleges, recruitment and supply agencies, professional development providers, multi-academy trusts, and ITT providers) are encouraged to commit to publishing institutional data on diversity and acting to address disparities.

Whilst these initiatives would be welcome additions, this leaves a gap in terms of accountability. The above analysis illustrates that, to an extent, ITT providers are already failing to ensure that increased diversity is supported over time. In addition to the recent reform to the Quality Requirements for ITT providers, the Government should introduce a requirement to the accreditation for ITT providers which mandates enhanced commitment to equal opportunities. This could be achieved through the regular review of recruitment and selection data and the introduction of corrective action when analysis shows disparities in outcome (subject to an agreed tolerance).

Reducing exclusions for children with SEN

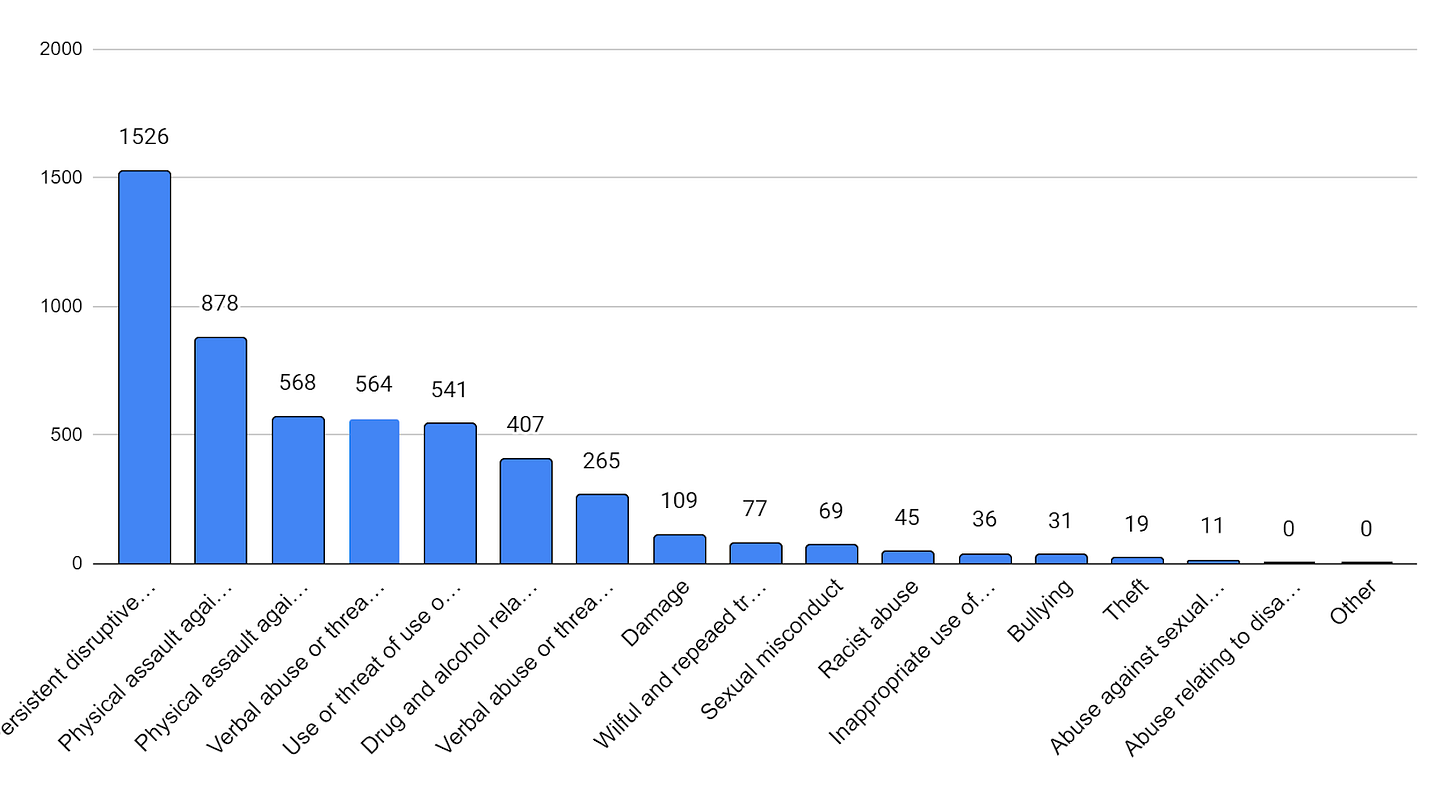

The most recently available data on permanent exclusions for school shows that the most common reason for expulsion is ‘permanent disruptive behaviour’.

Figure 18: Reasons cited for permanent exclusions during the academic year 2020/21. Source: Office for National Statistics.

As can be observed from figure 18, 29.65 percent of exclusions were attributed to this factor in the academic year 2020/21. In spite of this fact, there does not appear to be a standardised definition across the school system. The Child Mind Institute argues that disruptive behaviour is often misdiagnosed and that “in many cases, disruptive, even explosive behavior stems from anxiety or frustration that may not be apparent to parents or teachers”. This type of behaviour may stem from additional needs associated with conditions such as anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sensory processing problems, or other learning disorders. Charity I CAN has previously argued that children with speech and language challenges “are noted as having behaviour problems” all too often. However, given that data for suspensions and permanent exclusions indicate a significantly higher rate of segregative sanction for children with identified SEN, whether through statement or EHC plan, it may be that the driver for said disparity is not inability to identify such challenges in children. Rather, it may be the inability to address the underlying cause of perceived behavioural challenges which results in the over-exclusion of disabled children and children with SEN from the education system; that is to say that vulnerable children’s needs are not being met.

The Timpson Review of 2019 identified a number of studies which used qualitative methods to explore the experiences of autistic young people and their parents in and with the education system.

For example, a study with the National Autistic Society found both parent and child report a gradual decline in enthusiasm for the school system which deteriorated into hatred and resentment. This was attributed to schools either not appreciating or meeting the children’s needs. Such findings were consistent with those who spoke to parents of excluded children in London in 2015, finding a general sentiment amongst participants that mainstream schools “lacked the staff expertise, financial resources and time to accommodate pupils with additional needs”. Additionally, qualitative interviews with young autistic women and their parents in 2017, saw several themes emerging: schools were described as ‘impersonal’ and ‘inappropriate’ environments due to inappropriate peers, sensory processing difficulties and other pressures; challenges in communication and establishing positive staff or peer relationships; perceptions of inadequate understanding of needs amongst staff; and insufficient long-term support.

These sentiments are largely reflected in the Ofsted-Care Quality Commission (CQC) SEND inspections carried out between 2016 and 2021, in which a substantial proportion of schools were required to produce a written statement of action (WSoA) detailing plans to improve. In its evaluation report, the Government stated that the results of said inspections were “an indication of significant weaknesses in the local areas’ SEND arrangements.”.

.

Figure 19: proportion of local areas for which the SEND inspection resulted in the need for a WSoA. Source:Ofsted.

As can be observed from figure 19, just over half (51 percent) of local areas inspected in this five year period were deemed to require improvement in their provision of support for children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). The same report also appears to suggest that outcomes have become proportionately worse over time, excluding 2018-19 which saw the largest proportion of local areas (64 percent) receiving an unfavourable result. In 2022, data indicated that 76 out of 141 inspections had resulted in a WSoA. Inspection results have also varied significantly by region, with London seeing the lowest proportion of areas requiring a WSoA, followed by the East Midlands region. Conversely, the East of England region saw the highest proportion of areas requiring a WSoA, followed by North East, Yorkshire and Humber.

There are clear shortfallings of SEND provision at both the local and national levels, with quality of care and service provision as well as level funding consistently being highlighted as challenges. It is beyond the scope of this report to fully address the crisis currently gripping SEND provision and there is much work happening at the national level to support a redress of the system. However, examples of good practice offer hope for reducing the disproportionate rates of exclusions for children with SEND and, by extension, their exposure to CCE in lieu of a solution to the wider systemic issues referenced above. In recognition of the inequity and danger in such a situation persisting, agencies across Southwark, including the council, schools, colleges, health services, and safeguarding partnership agencies across the borough have produced the Southwark Inclusion Charter 2021. This document sets out the shared approach, principles, and commitments made by the respective signatories with “a recognition that permanent exclusion from education can have a significant negative impact on the wellbeing of children and their future”. Furthermore, one of the key commitments is that each agency, where appropriate, “will take a trauma-informed approach to behaviour of concern in children[...] not taking concerning behaviour at face value, but striving to understand what is driving that behaviour”. This is set against the acknowledgement that “there are rare instances where exclusion is unavoidable to safeguard children”. Such a document provides the terms of reference for a renewed commitment to limiting the damage done to children through exclusion, and should be adopted by local authorities across the country. The Southwark Inclusion Charter follows an exemplary record on exclusions, having reduced this number from 49 in 2017-18 to 36 in 2018-19 and further to 10 in 2020-21 through partnership working.